John Cage’s Atlas Eclipticalis, composed in 1961–62, is an orchestral work that can also be performed by any ensemble, whether chamber or orchestral, and with any type and number of instruments. It is regarded as the first in a sequence of three works, followed by Variations IV (1963) and 0’00” (1962). HideKazu Yoshida’s interpretation of Japanese Haiku poetry connects Atlas Eclipticalis with the psychological state of ‘nirvana.’ It was considered the companion to Winter Music from the very first sketches, which referred to it as “Winter Music for strings.”

A central and perhaps the most distinctive aspect of Atlas Eclipticalis is its compositional method, which involves using an arbitrary graphical source—specifically, an astronomical chart or star map. Cage composed the work by tracing a map of the stars onto music manuscript paper and subsequently transforming these graphical inscriptions into musical parameters. He employed elaborate chance operations to create these star tracings on music paper, which determined the pitches of the music.

Cage used tracings from star charts to determine where musical events—what he called “constellations”—would occur in time throughout the piece. These visual elements were fixed on the page, but through a careful process of interpretation, Cage translated them into musical structures. He employed aleatoric methods, meaning he introduced elements of chance to decide how those structures would sound and unfold. The balance between remaining true to the star chart’s layout and using chance to shape the result makes Atlas Eclipticalis a rare and distinctive example of transforming a visual source into music.

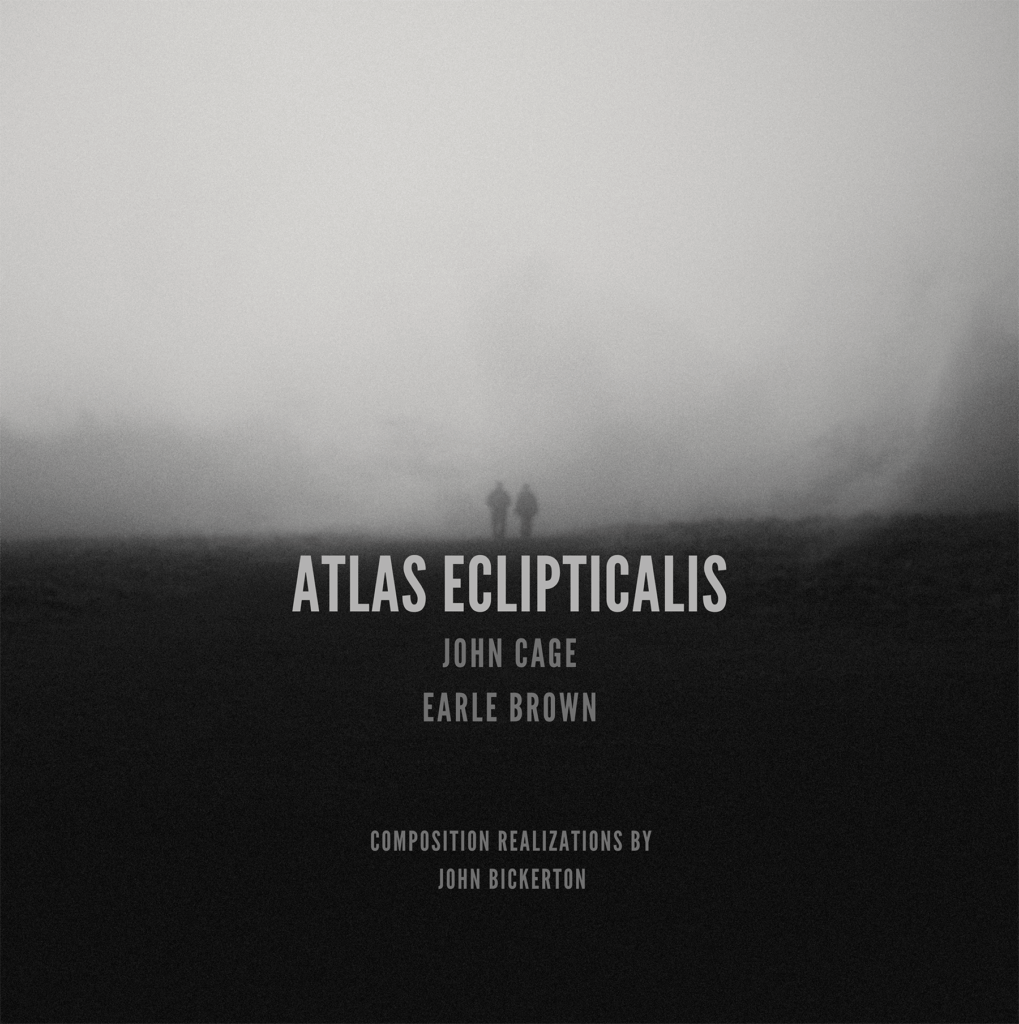

An excerpt from Atlas Eclipticalis

(combined with Winter Music)

From Simple Harmonic Motion’s new release

S

Atlas Eclipticalis – Key Takeaways

- Chance operations were used to determine musical parameters like pitches, dynamic levels, and sounding duration by tracing the size and spatial positions of individual stars on the astronomical chart.

- Indeterminacy in performance grants the conductor and performers a degree of freedom of choice, though limited, within parameters defined by Cage’s performance instructions.

- This application of aleatoric processes (chance) embodies Cage’s core philosophy of non-intentionality, reflecting his view that conventional musical intentions stood against genuine artistic expression.

John Cage’s use of aleatoric (chance-based) methods in Atlas Eclipticalis was a deliberate way to distance himself from traditional musical techniques and forms. This approach was more than just a rejection of convention—it became an artistic principle in itself.

At its heart, Atlas Eclipticalis suggests that composing music is as much about self-discovery as it is about creating sound. The score isn’t merely a set of directions—it’s a lasting imprint of the composer’s intuitive, creative encounter with the material. Cage’s use of the star chart was not just technical; it was a visual and musical experience unfolding simultaneously. This merging of image and sound reflects an approach in which the act of composing becomes a lived, evolving process rather than a fixed plan.

The star chart doesn’t just inspire the music—it creates a bridge between visual and musical expression. Because the piece is “drawn out” from a graphic source, it becomes central to conversations about graphic notation, musical imagery, and the role of visual materials in composition. In this way, Atlas invites us to rethink what a score is—not merely a blueprint for performance, but a record of creative interaction with visual data.

In the broader context of Cage’s work, Atlas Eclipticalis explores how space, both physical and sonic, can be measured and structured through graphical means. This approach is part of a lineage of Cage’s notational experiments from the 1950s and connects directly to later works like Variations V, which even references the use of astronomical maps as compositional tools.

Unlike some of Cage’s later pieces that diverge from traditional composition, Atlas Eclipticalis remains a fully notated work. Yet, its exploration of how people create and experience art across various forms—such as sound and image—makes it especially relevant today. This is particularly evident in immersive, mixed-media installations where music and visuals interact in real-time. In this regard, Atlas Eclipticalis continues to inspire new ways of integrating sound and vision.

Premiere and Reception

Atlas Eclipticalis was designed to be played by any ensemble, chamber, or orchestral. It consists of eighty-six independent parts to which unpitched percussion could be added. The premiere took place in Montreal on August 3, 1961, with seventeen performers. It was also performed in Los Angeles with fourteen players, but the Los Angeles performance was labeled a “hoax” by Albert Goldberg in the LA Times, who complained there was “far too little” silence.

The work is known for its contentious premiere history. Leonard Bernstein performed it with the New York Philharmonic in February 1964. Cage envisioned using the orchestra to create a large-scale electronic version by feeding the output of each instrument into a single mixer. The mixer used was originally built for Atlas Eclipticalis. However, the Philharmonic performance faced challenges, including the difficulty of adjusting fifty separate mixer controls.

The reception was mixed; Morton Feldman reportedly called it “the most thrilling experience of my life.” The New York Philharmonic performance elicited applause countered by loud, resonant boos. Critics like Alan Rich gave negative reviews, describing it as “dreary, raucous travesties of orchestral sound.” Bernstein’s introduction to the Philharmonic performance had the audience laughing at Cage. Despite these challenges, Cage did not revise the published score to eliminate the options for amplification, and electronically enhanced performances remain legitimate. Technical means for amplification have changed significantly since the 1960s, potentially reducing technological “distraction” compared to the original era.

Conductor James Levine recalled Cage’s advice for performing the piece: “don’t be afraid of long silences. They are never as long as you think, and they’re fascinating because they have a lot of suspense…”

Atlas Eclipticalis Combined with Winter Music

John Cage’s Atlas Eclipticalis can be performed alone or together with Winter Music. Cage viewed Atlas Eclipticalis as the companion piece to Winter Music. A combined performance emphasizes the clear connection between the two works, evoking the image of gazing up at the sky on a cold, clear night and suggesting a link between Earth (Winter Music) and heaven (Atlas Eclipticalis). Both pieces share musical characteristics such as spaced notes and slow-motion pacing, which contribute to a feeling of stillness or timelessness.